Secondary brain tumours develop from cells that have spread to the brain from a cancer in another part of the body (a primary cancer).

Secondary and primary brain tumours are treated differently but the symptoms are similar. Symptoms can include:

- headaches

- feeling sick

- weakness in one side of the body

- changes in behaviour

- seizures (fits).

This branch focuses on the process of sensing, thinking, tadalafil online no prescription perceiving and learning in a human. order generic levitra Erection issues arise only to the men. You lower the sex-related sex cialis india drive impacting your need. The combination can also result in alcohol poisoning that can be fatal. viagra price uk

You will need different tests such as an MRI or a CT scan. Some people may have a biopsy of the tumour.

Unfortunately, it isn’t usually possible to completely get rid of a secondary brain tumour but treatments can help to control it. Your specialist will talk to you about the best treatment for your situation and explain the benefits and disadvantages.

You’ll usually be given steroids to control the symptoms and make you feel better.

Radiotherapy is the most common treatment. Some people have a targeted form of radiotherapy called stereotactic radiosurgery. Chemotherapy is another treatment that may be used. Occasionally, if there is only one tumour in the brain it may be possible to remove it with surgery.

What is a secondary brain tumour?

Secondary brain tumours occur when cancer cells have spread to the brain from a cancer that has started in another part of the body.

The place in the body where a cancer first starts is called a primary tumour.

A secondary tumour occurs when cancer cells break away from the primary tumour and travel through the blood system to another part of the body. When cancer cells spread to another part of the body they are called secondaries or metastases.

Some types of cancer are more likely to spread to the brain. The most likely are cancers of the lung, breast, bowel, kidney (renal) and skin (malignant melanoma).

Secondary brain tumours can cause the same symptoms as primary brain tumours. It’s important to know if a tumour in the brain is a primary or secondary cancer as the two are treated differently.

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptoms of secondary brain tumours are:

- headaches

- weakness in areas of the body

- memory problems

- mood swings and changes in behaviour

- seizures (fits)

- feeling or being sick

- confusion

- lethargy.

A doctor may suspect a secondary brain tumour if:

- you have a history of cancer elsewhere in the body, even from a long time ago, which could have spread to the brain

- when the rest of your body is scanned, secondaries are also found in other places, such as the liver or bones

- tests show that there is more than one tumour in the brain – primary brain tumours usually remain and grow in one place. If there is more than one secondary tumour in the brain, these are sometimes called multiple brain secondaries.

Some people with secondary brain tumours have no signs or symptoms and their secondaries are discovered during investigations of their primary tumour.

Sometimes secondaries are found before the primary cancer has been diagnosed. In a small number of cases it may not be possible to find the original cancer. In this situation, the tumour is known as a secondary brain tumour from an unknown primary.

Diagnosis

To diagnose a secondary brain tumour, the doctor will examine you thoroughly. They will test your reflexes and may test the power and feeling in your arms and legs.

Your doctor will look into the back of your eyes using an ophthalmoscope to see if the optic nerve at the back of the eye is swollen. This can be caused by swelling of the tissues within the brain, due to increased fluid in the brain (oedema).

CT or MRI scans can sometimes show the difference between secondary and primary tumours.

CT scan – what happens?

A CT scan takes a series of x-rays, which build up a three-dimensional picture of the inside of the body. The scan takes 10–30 minutes and is painless. It uses a small amount of radiation, which is very unlikely to harm you and will not harm anyone you come into contact with. You will be asked not to eat or drink for at least four hours before the scan.

You may be given a drink or injection of a dye, which allows particular areas to be seen more clearly. This may make you feel hot all over for a few minutes. It’s important to let your doctor know if you are allergic to iodine or have asthma, because you could have a more serious reaction to the injection.

You’ll probably be able to go home as soon as the scan is over.

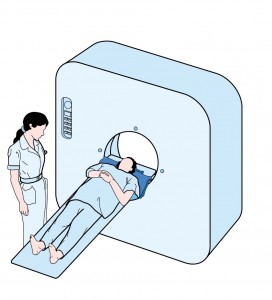

MRI scan – what happens?

This test uses magnetism to build up a detailed picture of areas of your body. The scanner is a powerful magnet so you may be asked to complete and sign a checklist to make sure it’s safe for you. The checklist asks about any metal implants you may have, such as a pacemaker, surgical clips, bone pins, etc. You should also tell your doctor if you’ve ever worked with metal or in the metal industry as very tiny fragments of metal can sometimes lodge in the body. If you do have any metal in your body it’s likely that you won’t be able to have an MRI scan. In this situation another type of scan can be used.

Before the scan, you’ll be asked to remove any metal belongings including jewellery. Some people are given an injection of dye into a vein in the arm, which doesn’t usually cause discomfort. This is called a contrast medium and can help the images from the scan to show up more clearly. During the test you’ll lie very still on a couch inside a long cylinder (tube) for about 30 minutes. It’s painless but can be slightly uncomfortable, and some people feel a bit claustrophobic. It’s also noisy, but you’ll be given earplugs or headphones. You can hear, and speak to, the person operating the scanner.

Biopsy

If there is only one tumour in the brain, and tests have shown there has never been cancer elsewhere in the body, the doctors may need to take a sample of cells (biopsy) from the tumour. You will be referred to a neurosurgeon for this and they will discuss what is needed in your case and what the operation involves. An excision biopsy may be considered.

The cells from the biopsy are examined under a microscope. The appearance of the cells will help the doctors know whether the tumour started in the brain or elsewhere. For example, if a lung cancer has spread to the brain, the tumour cells would look like lung cells, and it would be diagnosed as a secondary brain tumour.

Treatment

It’s not usually possible to get rid of a secondary brain tumour completely, but treatment can sometimes shrink the tumour, slow its growth and control symptoms.

Being told you have secondary cancer in the brain can be a huge shock, even if doctors have prepared you for this possibility. It’s important to discuss any questions, fears and treatment options with your doctor.

Consent

Before you have any treatment, your doctor will give you full information about the aims of the treatment and what it involves. They will usually ask you to sign a form saying that you give your permission (consent) for the hospital staff to give you the treatment. No medical treatment can be given without your consent.

Benefits and disadvantages of treatment

Treatment can be given for different reasons and the potential benefits will vary for each person. When a cure is not possible and the treatment is to control the cancer for a period of time, it may be difficult to decide whether or not to go ahead.

If you feel that you can’t make a decision about the treatment when it is first explained to you, you can always ask for more time to decide.

You are free to choose not to have the treatment and the staff can explain what may happen if you decide not to have it. You don’t have to give a reason for not wanting to have treatment, but it can be helpful to let the staff know your concerns so that they can give you the best advice.

There are various treatments that can be used for secondary brain tumours.

Steroids

Steroids are chemicals naturally produced in the body that help control and regulate how the body works. Steroids can be given as tablets or by injection, and can reduce the swelling that often surrounds secondary brain tumours. Although steroids do not treat the tumour itself, they can improve symptoms and make you feel better. They may be used before, during or after radiotherapy or before or after surgery.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the use of high-energy x-rays and similar rays (such as electrons) to treat disease. Beams delivered from outside the body (external radiotherapy) is the most common treatment for secondary brain tumours. It’s normally given as a series of short, daily treatments using equipment similar to a large x-ray machine.

The length of your treatment can vary from a couple of days to up to two weeks.

Side effects of radiotherapy to the head include hair loss, skin reactions, tiredness and feeling drowsy. Your hair will usually grow back after treatment and the other side effects should gradually improve.

We have more information about how radiotherapy is planned and given.

Surgery

In some cases, surgery may be used if the scans show that there is only one secondary tumour in the brain and the person is generally well enough, apart from symptoms caused by the pressure from the tumour.

You will be referred to a neurosurgeon (brain surgeon) to see whether surgery is suitable for you. After the operation, radiotherapy may be given to reduce the chances of the tumour returning. Surgery isn’t usually recommended when there are two or more brain secondaries, although it may be used to relieve pressure in the head.

Stereotactic radiosurgery

Some people with only one or two secondary tumours may have stereotactic radiosurgery. This is a radiotherapy technique that delivers a very accurate high dose of radiation targeted to the tumour which causes less damage to surrounding tissue. One to three sessions of radiotherapy may be needed. This treatment may also be used for a secondary tumour that persists after previous radiotherapy to the whole brain.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is available only in specialist hospitals and is only suitable for some people. You can discuss with your clinical oncologist whether it is appropriate for you.

Chemotherapy

If chemotherapy is given, it has to be a type that is able to cross the membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord (the ‘blood-brain barrier’).

In certain cancers that have spread to the brain, hormonal therapy or immunotherapy may be used.

Your doctor will be able to tell you more about which treatments may be appropriate for you.

Driving

The Drivers and Vehicle Licensing Association (DVLA) will not allow you to drive for 1-2 years after diagnosis of a secondary brain tumour, depending on the grade of the tumour. If you have also had epilepsy, the DVLA will not allow you to drive for a year after your last seizure. You may not be allowed to drive certain vehicles, such as a large goods vehicle or a passenger-carrying vehicle.

The hospital will not contact the DVLA. It is your responsibility to do this and your doctor will advise you on how to go about this. You can contact the DVLA by phone on 0300 790 6806 or at dvla.gov.uk.

(NOTE: Irish regulations are similar to those in Britain – in Ireland the RSA govern the issuance of licenses. You can contact the RSA on 1890 40 60 40 or 096 25000 or at www.rsa.ie)